IPADE’s Operations Management Professor, Miguel León shares his highlights about the Mexican Auto Sector and its future.

In 2015, Mexico assembled more than 3.5 million vehicles, making it the world’s seventh-largest manufacturer. But global automotive giants have even bigger plans in store: According to AMIA, Mexico’s automotive industry association, and ProMexico, its trade promotion agency, Mexico is on track to assemble four million units (including light and heavy vehicles) by 2018 and five million units by 2020. All of the big American, Asian and European global automotive groups now have a presence in Mexico, including Hyundai, Volkswagen, Renault, Nissan, Toyota, Mazda and Honda.

Foreign investors have pumped billions of dollars into the Mexican automotive sector in recent years due to its proximity to the United States, and the fact that Mexico maintains free trade agreements not only with the United States and Canada (via the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA), but also with the European Union and the nations of Central America and Mercosur, the South American trade pact. In addition, Mexico has a relatively low cost for skilled labor, which compensates for the logistical costs involved in moving components and assembled vehicles in and out of the country.

Most vehicles assembled in Mexico are shipped to the United States, for which Mexico is the third-largest supplier of imported cars, exceeded only by Germany and Japan, according to the office of the U.S. Trade Representative. Over the first 10 months of 2016, 86.1% of Mexico’s automotive exports were shipped to its NAFTA trading partners, according to AMIA. But with the inauguration of Donald Trump, who made building a wall between the United States and Mexico a key part of his presidential campaign, could Mexico’s automotive sector be at risk? The question seems inevitable: Could Mexico wind up losing its competitive advantage in the sector because of U.S. protectionist measures?

A Wide Range of Trade Pacts

On the one hand, some automotive industry experts believe that Mexico’s dependence on selling vehicles to the U.S. market will continue despite threats of protectionism, and even expand in the coming years. A few months ago, Ford announced that it would move all of its production of small models from Michigan to Mexico. That decision was harshly criticized by Trump, who threatened to impose U.S. import tariffs of 35% on cars produced in Mexico. “That sort of tariff would be imposed on the entire automotive sector, and it could have an enormous impact on the United States economy,” Mark Fields, Ford’s chief executive, said after a speech at the AutoMobility conference in Los Angeles in November, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Brad McBride, a professor at the Mexico City-based Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology (ITAM), notes that if Trump follows through on his proposals, the impact on Mexico’s automotive industry will be significant. “As a result of a tariff on the importation of autos and components, many producers would relocate a large share of the products that they export to the Southeast — the Carolinas, Alabama, Tennessee and Georgia. This region would enjoy a big comparative cost advantage if Mexico imposes tariff barriers in retaliation for the U.S. tariffs, he adds.

According to Miguel Leon, dean of operations at IPADE, the business school at Pan-American University in Mexico City, the imposition of high tariffs on Mexican exports could lead to the cancelation of automotive shipments to the U.S. by American companies and consequently, “to a shortage of supply in certain products on the American market.” Leon says that if such measures were to be carried out, American manufacturers would have two options: Either jointly absorb the cost of the new tariff along with their distributors in the U.S., or redirect their global production strategy, taking advantage of the free trade agreements that Mexico has signed with numerous other countries around the world. As of January 2017, Mexico has a network of 10 free-trade agreements with 45 different countries; 32 reciprocal investment promotion and protection agreements (RIPPAs) with 33 countries; and nine trade agreements with the framework of the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI). Mexico also has signed up for membership in the controversial 11-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), but if the Trump administration opts to withdraw from the pact, the resulting absence of the U.S. would effectively lead to the TPP’s demise, trade analysts say.

Leon notes that the damage to Mexico from U.S. protectionism would be significant because nearly 80% of Mexican automotive exports are shipped to the U.S. Moreover, the automotive sector represents about 3% of Mexico’s GDP and 18% of its manufacturing GDP. Nevertheless, Leon adds that protectionist measures undertaken by the Trump administration could ultimately have a boomerang effect that winds up damaging the United States as well as Mexico.

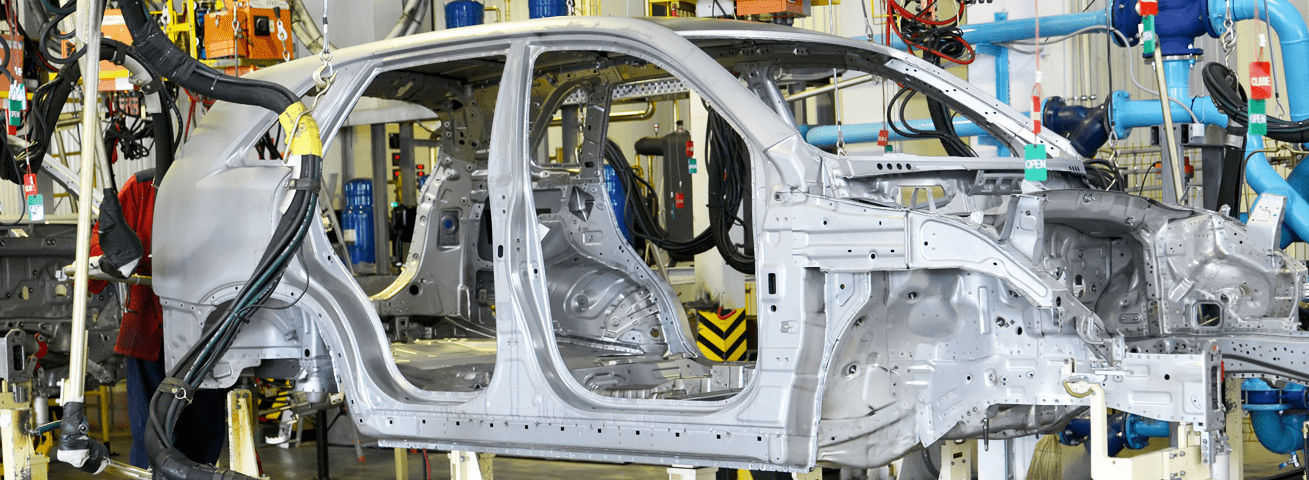

“Mexican industry bases its productivity and competitiveness on its localization, on the youth of its labor force, and on a great tradition of vehicle assembly that goes back to 1927, when Ford produced its first car in Mexico,” Leon says.

“[Mexico’s] capacity to deliver vehicles in accordance with world-class programs of cost and quality … makes it very competitive. For that reason, if the United States were to stop buying from Mexico, it would be much costlier for the United States. The supplying of vehicles to the United States would probably be left to China.”

McBride notes that the process of relocating this lost production would be damaging not only to central Mexico — where many of the new foreign plants are located — but also to Mexico’s northern states, which have prospered during the 22 years of NAFTA’s existence. “In fact, a large part of the country’s north looks like a first-world economy, especially the state of Nuevo Leon,” whose capital is Monterrey, McBride adds. “That’s because of the manufacturing economy created by trade with the United States. There is a growing middle class in Mexico, but it is probably still not enough to create enough demand to substitute for [lost Mexican] exports to its neighbor to the north.” As a result, such a blow to Mexico’s automotive industry would be “terribly negative” for Mexico, McBride says, and would become “a serious impediment to its future growth.”

The good news for Mexico, according to Leon, is that over the next five years, “it does not seem possible that the big [foreign automotive] brands will freeze [the value of] their investments” there. Indeed, over the short term, it would be impossible for major global manufacturers to substitute for their Mexican production capacity by expanding their capacity elsewhere, while maintaining the same level of quality at a similar cost. McBride agrees with that view, although he says that there are other reasons why U.S. manufacturers would not leave Mexico, even if high tariffs were imposed by the U.S. “There is a significant and growing internal market in Mexico,” he points out. Nevertheless, McBride says that it is possible to reduce production levels in Mexico, substituting that with production growth in the southern United States, “an area that is economically competitive, and where there is not a lot of union activity.”

But Jorge Arturo Yescas Hernández, a professor of industrial and mechanical engineering at the University of the Americas in Puebla (UDLAP), says that certain brands might think twice before investing money in Mexico. In the specific case of BMW, he says that “if [BMW] takes into account that the initial proposal would consist of supplying the Latin American market, then the effect would not be so big that it would paralyze its investments.” He notes that the competitive position of Mercedes-Benz, for example, could be quite different, since its intention is to set up on Mexican soil in order to sell to the American market. “In that case, investments would definitely be affected.”

Hernández anticipates a significant economic slowdown in Mexico if Trump’s tariff talk becomes reality. To counter the negative effects of such a policy, Hernandez proposes that Mexico “immediately begin to create national brands, and promote their development through their incorporation to the needs of governmental transportation.” He says that the country clearly has the technology and trained personnel to move forward with initiatives of this sort. Experts at various institutions, such as the Ministry of the Economy, AMIA and BANCOMEXT, the country’s national foreign trade bank, have said they agree with that approach.

But the doomsday scenario about the impact of the Trump administration on NAFTA — and on Mexico — is not so clear, according to Wharton management professor Mauro Guillen. First, critics of NAFTA often overlook — or minimize — the fact that NAFTA is a three-way agreement, involving Canada, as well as Mexico and the United States. For Canada, which shipped 76.7% of its exports to the United States in 2015, “nothing would be more disruptive than renegotiating NAFTA,” Guillen notes. A lot of companies in Canada, including U.S. and European firms invested in that country, rely on NAFTA as a cornerstone for their North American strategies. Moreover, commitment to bilateral free-trade between the U.S. and Canada predates NAFTA. It is a “longstanding thing that goes back prior to NAFTA,” first formalized in the U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement in the late 1980s, Guillen points out.

Guillen adds that if the U.S. and Mexico were to renegotiate the terms of NAFTA in such a way that a sizable number of U.S. and other foreign manufacturers actually did move their plants out of Mexico, that would not necessarily mean that those plants would wind up returning to the United States. “You can renegotiate something with Mexico, but then the manufacturing, instead of being in Mexico, could [wind up] somewhere else — such as Costa Rica or Vietnam,” he notes.

Potential Policy Disagreements

As Trump prepares to take power, there remains widespread doubt about precisely which new directions U.S. trade policy will take under his leadership. As Guillen points out, no U.S. president, including the assertive and iconoclastic Trump, can “change trade policy unilaterally, just like that. It is up to the Congress” as well as the president and trade policy experts in various bureaucracies and think tanks. Although Republicans control both chambers of the U.S. Congress, “There is one part of the Republican Party that is more populist and wants to increase protection, but there is another part that is more pro-business and pro-free trade,” notes Guillen. Similar disagreements can be found within the Democratic Party, he adds. “Unless the protectionists in both the Republican and Democratic parties get together, I don’t think there is going to be a big change.”

Even among the ranks of Trump’s cabinet appointees, there are signs of significant policy disagreements that make it difficult to predict where the new administration will move on matters of trade policy toward Mexico and other trade partners. For example, although Wilbur Ross, the billionaire investor tapped by Trump to become U.S. Secretary of Commerce, has vowed to pursue Trump’s “America First” trade policy, Ross’ key policymaking role in the Trump administration could create friction among trade specialists by undercutting the traditionally strong policymaking role of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative under previous presidents, both Republican and Democrat.

Moreover, on occasion Ross has espoused views on trade that seem antithetical to Trump-style protectionism. In 2015, Ross signed a letter in support of the TPP deal, which Trump has said he opposes. And in 2012, Ross argued in an interview that “China bashing is widely overdone in this country,” and that if China were to significantly upwardly revalue its currency, “those jobs are not going to come back to the U.S.” In a statement that could augur well for supporters of free trade with Mexico and elsewhere, Ross then added, “The way we’ll get more jobs [in the U.S.] is by creating new industries, new companies, businesses that are higher tech and therefore can compete.”

On another recent occasion, Ross said that his goal won’t be to punish U.S. companies that produce goods in Mexico, but to reduce America’s trade deficit with Mexico. The U.S. market, he added, accounts for 80% of Mexican exports, which gives the United States lots of leverage to lean on its southern neighbor to buy more American-made products. “If I’m a guy’s 80% customer, is he going to fight with me?” Ross said. “No, he’s going to negotiate.” He later promised, “There aren’t going to be trade wars” with Mexico, after all.

This article originally appeared in Knowledge@Wharton